mermaidcamp

Keeping current in wellness, in and out of the water

You can scroll the shelf using ← and → keys

You can scroll the shelf using ← and → keys

To catch a falling leaf on Halloween

Requires stealth and cunning beyond measure

To capture the essence of this seasonal luck

Concentrate fully on your goals and wishes

With visions of success for all your relations

Shooting commandments from the asphalt

Moses makes an effort to convey

Deep meaning and portents

To these pronouncements of responsibility

His efforts fall flat

Unwilling and unwitting,

Populations trudge along

Taking no heed of conditions

Trying to avoid at all costs

The damage being caused by denial

Returning to dissolve potential

The phrase gilded age came from the title of a humorous novel written by America’s undisputed king of wit. It was written with fellow author Charles Dudley Warner to satirize the state of affairs after the Civil War.

We are listening to the audio book, produced as a radio play, using different voices for the characters. The book comes alive as the actors portray well defined parts in a well told tale of high comedy in a historic setting. The descriptions of daily lives are vivid enough to make the listener part of the action. The dialog defines each player to the T.

I’m writing this before finishing the book (Twain and Warner wrote in the forward that they expected to have the book reviewed without being read). It is a perfect book for our times. The writing reminds us that history repeats itself with regularly. I highly recommend reading it now, for insight and lots of laughs.

Tides turn every day, following the moon

The forces that surge ahead

Eventually, predictably reverse course

Every wave is different

Many not suitable for riders

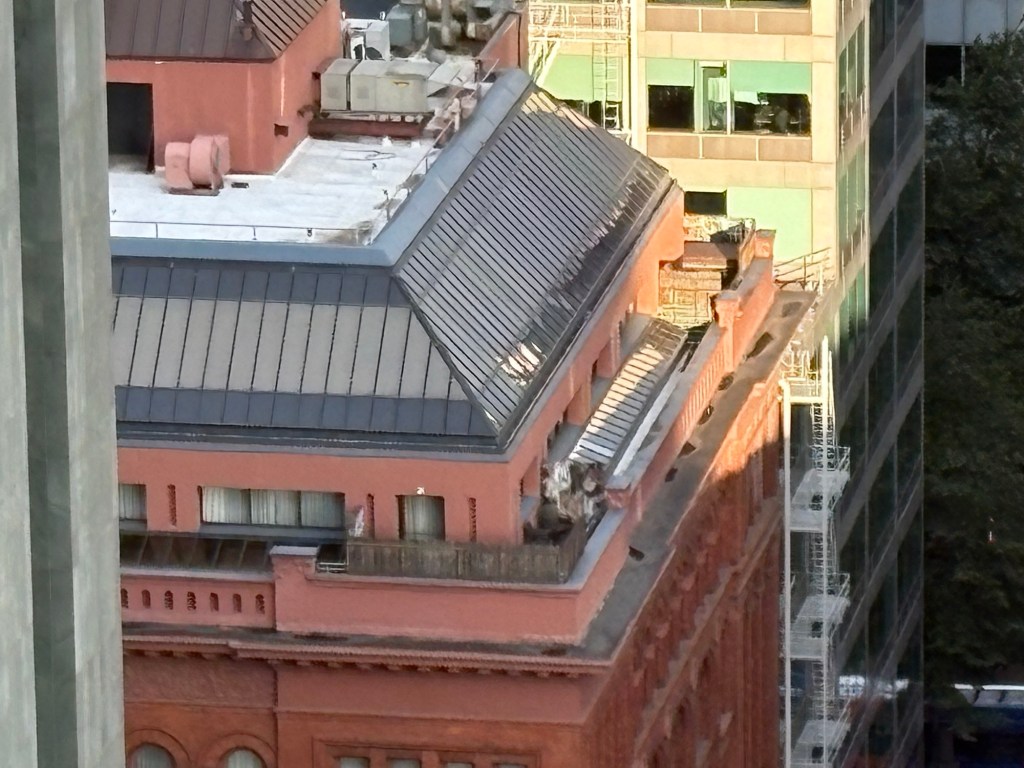

The oldest hotel in Portland, Oregon is known now as Kimpton Vintage. When it opened in 1894 it was called the Imperial Hotel. Its history includes expansion and contraction through changes in ownership. I particularly enjoy the architecture of that period, which was built when the city was riding high. I have stayed in other Kimpton properties, which I admire for the reform and restoration of historic structures. Kimpton Vintage Portland is a shining example of artful design that creates an atmosphere of elegance and hospitality.

We had a wonderful visit in an elegant corner room before a long train journey. The front desk agent, Ben, convinced us to return at the end of our trip. We asked him what was happening on the 9th floor on the balconies. He told us about the jacuzzi suites available, then booked one for us.

This was a perfect grand finale to our trip. The hotel has a daily complimentary wine happy hour with excellent local wines. The convivial lobby event gives guests a cozy way to meet each other. We met a fellow guest who had borrowed the free bike the hotel offers to ride across the bridge to survey the city.

Too many superb options exist for dining within walking distance of the hotel. We only had time to visit a couple old favorites on our stay.

I love staying downtown Portland to experience history in a modern context. I have now found the perfect place to enjoy that. It’s a short walk to the waterfront, my fave place to stroll. Public transportation is super convenient and efficient. Cosmopolitan living at its finest is available for visitors to the Rose City. Dogs are welcome.

Recently public discourse has been a great concern of mine. Some on line acquaintances have chosen to leave platforms or go dark. When one of my friends of many years announced his departure he published an excellent essay about living presence as opposed to on line activity. His words moved me but I was unhappy to lose a view of his daily life.

After consideration of his well written thoughts on privacy and awareness I decided to stay but make new use of the platform I have now. The poet who writes here is a part of my archetypal make up. It’s an artistic skill I want to develop as a tribute to my famous poet ancestor, Anne Dudley Bradstreet. I decided to channel myself into this practice in order to extract myself from the current political debate. I have not found participation in on line politics to be fruitful use of my time or energy. It seems to be a catalyst for social collapse.

I’m sticking with the idea that writing poetry is the most effective method of self care I know. It’s my current way to communicate on the internet without generating vexation. I certainly hope I become better at it, but for now it’s what I do. When I take care of dogs I sing improvisation dog songs in which my current client is the star. They often begin with so and so is a good dog, a funky good dog. They always get it and have no criticism of my work.

Whisper sea shanties and sing to the fish

Stars reflected on surface waves all night

Sun signals a clean sweep for today

The robot wants me to prove I am human

I want the robot to prove to me it is valid

How many crosswalks will this require?

This season of flowering abundance

Is created by the attention paid

To the details we draw on the surface

As the core reality is shaken by dramatic events